Much of what happens in nature is described through what we can see: humpback whales breaching, sea lions hauled out on shore, and large schools of fish swimming in sync through the water. But beneath all the visible interactions is an unseen world that makes all ocean life possible, and at times, puts it at risk.

Marine mammals live in complex microbial environments. Every breath, every dive, and every meal brings them into constant contact with microscopic organisms that influence their bodies and the ecosystems they depend on.

Microbes as Beneficial Companions

From birth to death, marine mammals coexist with bacteria, viruses, archaea, protists, and fungi, making up 90% of the ocean’s living biomass. Much like us, marine mammals skin, digestive systems, and respiratory tracts are home to microbiomes that aid daily survival. These microorganisms are not just along for the ride for their own benefit: they interact closely with their hosts, affecting digestion, immune function, and even how animals respond to their environment.

A humpback whale beneath the surface. Among the studied mammals, baleen whales, like humpbacks and blue whales, are recognized for having especially complex gut microbiomes, highlighting the role of microorganisms in digestion. Courtesy of Chinh Le Duc, Unsplash

Genetic sequencing studies comparing marine mammals to their surrounding seawater show that microbial communities are not only apparent, but also species-specific, shaped by diet, behavior, physiology, and evolutionary history. These studies suggest long-term relationships, rather than random or accidental exposure.

Skin microbiomes are especially important. Marine mammal skin is in constant contact with seawater that contains pathogens, pollutants, and toxins. Microbes on the skin form a biological “shield,” potentially limiting colonization by harmful bacteria leading to disease and outbreaks.

The respiratory tract is another critical point of microbial interaction. Marine mammals breathe at the ocean’s surface, taking in air through their blowholes or nostrils. This exposes them to not only organisms in the water but also aerosols and organisms in the air. Microorganisms come into close touch with the respiratory systems with every breath, building a unique internal ecosystem that is molded by both the water and air. While research in this area is still emerging, studies suggest that respiratory microbiomes may influence susceptibility to infection and play a role in respiratory health, particularly in species that surface more frequently or live in environments with higher concentrations of pathogens and pollutants.

In healthy mammals, microbiomes across the skin, gut, and respiratory tract tend to be diverse but often unchanging. These beneficial organisms fight for space and host resources with possible pathogens, which lowers the risk of infection. These relationships help marine mammals deal with the frequent exposure to microbes that comes with life in the ocean.

Microbiomes also respond quickly to physiological stress. Pollution, reduced prey, chemical exposure, and warming waters have all been linked to physiological stress in marine mammals, and microbial changes may serve as early signs of these pressures. This has led researchers to explore microbiome monitoring as a non-invasive tool for determining population health, particularly in species that are difficult to sample or observe closely.

However, the same pathways that allow microbes to support digestion, immunity, and respiration also lead to points of vulnerability. When the balance of microbes is off, these routes of interaction can expose marine mammals to toxins, pathogens, and disease.

Microbes as Agents of Harm

Unlike visible threats such as ship strikes, entanglement, and noise pollution, microbial harm almost always begins invisibly. When conditions favor harmful germs or pathogens, everyday interactions can lead to illness, reproductive failure, and large-scale mortality events.

Domoic Acid and Neurotoxin Exposure

One of the most direct ways microbes harm marine mammals is through toxin production that moves through the food web. On the west coast of the United States, blooms of the diatom Pseudo-nitzschia produce domoic acid, a strong neurotoxin that builds up in fish like anchovies and sardines. These prey species often show no outward signs of illness, allowing the toxin to move unnoticed into higher trophic levels.

When marine mammals consume infected prey, domoic acid crosses the blood–brain barrier, leading to a loss in neurological function. California sea lions exposed to domoic acid are found frequently stranded with seizures, disorientation, abnormal behavior, and in severe cases, permanent brain damage or death. During major bloom years, hundreds of sea lions have stranded in a single season, underscoring how quickly microbial toxins can translate into visible population-level impacts.

California sea lion stranded on Ventura County Beach from Domoic Acid poisoning. Courtesy of Hazel Rodriguez, USFWS

Research has shown that chronic, low-level exposure to domoic acid can impair memory and navigation and has also been linked to increased miscarriage rates in female sea lions. This means the effects of a bloom may persist long after the event itself, influencing reproductive success and long-term population health.

To better understand the long-term impacts of domoic acid, researchers are combining stranding data with neuroimaging, hormone analysis, and long-term monitoring of exposed animals. Studies of rehabilitated sea lions have used brain imaging and behavioral testing to document lasting neurological damage, even in animals that appear recovered. Other research tracks pregnancy outcomes and pup survival in exposed females to understand how toxin exposure affects reproduction over time.

Despite decades of study, many questions remain. Scientists are still working to determine how repeated low-level exposure accumulates across an animal’s lifetime, how exposure thresholds vary by species, and how climate-driven changes in bloom timing intersect with critical life stages such as pregnancy and migration. As harmful blooms become more frequent, understanding these chronic effects is increasingly important for predicting population-level consequences.

Harmful Algal Blooms

Domoic acid is only one example of harmful algal blooms (HABs). These blooms occur when certain species of algae grow rapidly under favorable conditions, producing toxins that affect entire ecosystems. Marine mammals are rarely exposed directly to these algae and instead become exposed as the toxins accumulate in their prey.

In the Gulf of Mexico, blooms of Karenia brevis, commonly known as red tide, produce brevetoxins that affect marine mammals through both ingestion and inhalation. Unlike many toxins that require consumption, brevetoxins can become aerosolized, exposing marine mammals when they surface to breathe. This dual exposure potential increases risk even when feeding activity is reduced.

During red tide outbreaks, large marine mammal mortality events have been documented, including a single outbreak that wiped an estimated 10 percent of the Florida manatee population in the 1990s. These events highlight how algal toxins can severely decimate even well-adapted species, especially when blooms persist for weeks or months.

Harmful algal blooms have increased in frequency, duration, and geographic range in many regions, closely linked to warming waters and nutrient runoff. As bloom conditions expand, so does the window of exposure for vulnerable marine mammals.

Research on harmful algal blooms relies on early detection and forecasting. Satellite imagery, coastal monitoring stations, and microscopic tools are now used to track bloom formation and toxin production in real time. These efforts help scientists link bloom conditions to marine mammal strandings and identify which prey species are most likely to transfer toxins up the food web.

However, predicting when and where blooms will become dangerous remains challenging. Different algal species respond to temperature, nutrients, and circulation in different ways, and toxin production does not always correlate with bloom size. Continued research is needed to improve bloom detection and forecasting, understand how toxins move up marine food webs, and identify which regions and species face the highest risk as ocean conditions continue to change.

Bacterial Pathogens and Chronic Infections

Not all microbial harm is fast or easily identifiable. Bacterial infections can cause chronic, systemic infections that are harder to detect and often go unrecognized. One of the best-studied examples is marine brucellosis, caused by the bacteria Brucella ceti and Brucella pinnipedialis.

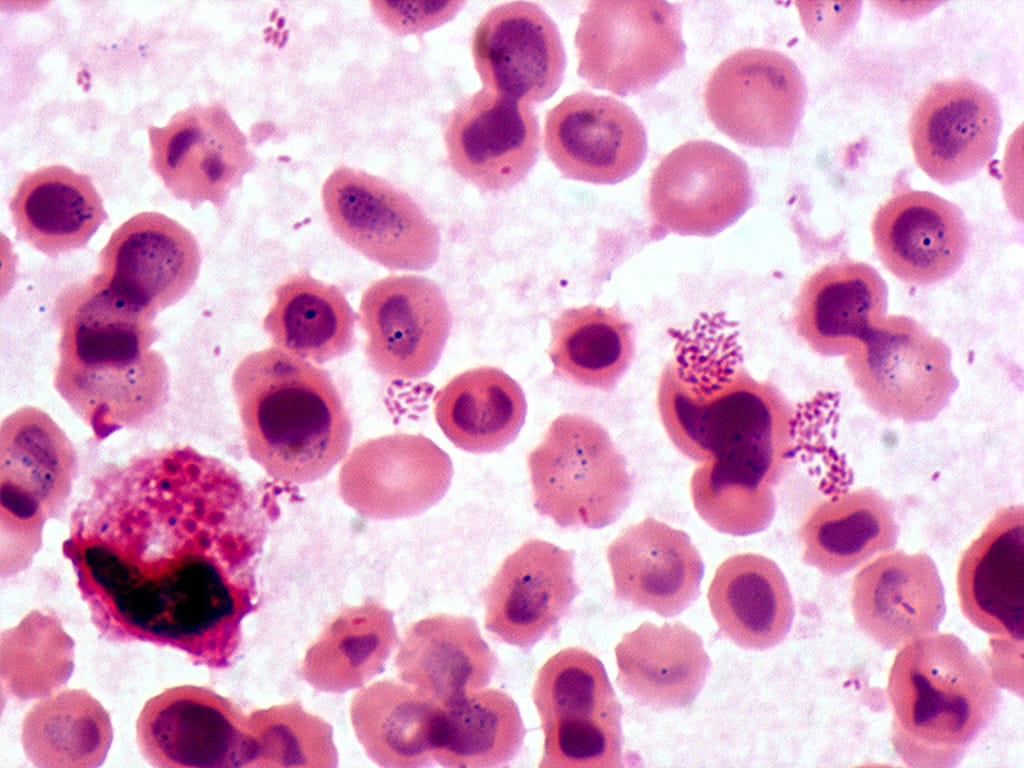

Microscopic image showing Brucella bacteria clustered in host immune cells. While not marine-mammal-derived, this image illustrates the same intracellular survival strategy used by Brucella ceti in cetaceans. Courtesy of Microbe Canvas

These bacteria have been isolated from whales, dolphins, seals, and sea lions worldwide. Serological reports shows exposure is widespread across populations, even when animals appear physically healthy. In some cases, however, Brucella infections can lead to serious outcomes, including miscarriage, neurologic disease, pneumonia, and bone infections.

Unlike algal toxins, which often cause acute illness, bacterial infections may persist for long periods. Subclinical infections can weaken immune systems, reduce reproductive success, and increase susceptibility to other stressors.

Studying bacterial disease in marine mammals presents unique challenges. Many infections are chronic or subclinical, meaning animals may carry bacteria for long periods without obvious signs of illness. Researchers rely on necropsies, serologic surveys, and molecular diagnostics to detect infections such as Brucella and determine how widely they are distributed across populations.

Ongoing research aims to clarify how bacterial infections interact with other stressors. Scientists are also working to understand transmission pathways, including whether bacteria persist in the environment or are passed primarily through close contact. Filling these gaps is critical for determining when bacterial pathogens pose a population-level threat rather than an isolated case.

Viruses represent a rapidly emerging microbial threat to marine mammals, especially as climate change alters disease dynamics and host susceptibility. In recent years, highly pathogenic avian influenza (H5N1) has crossed from birds into marine mammals, causing mass mortality events.

During the 2023 outbreak in Argentina, H5N1 killed more than 17,000 southern elephant seal pups, one of the largest documented viral outbreaks in marine mammals. Similar outbreaks have affected sea lions and seals across multiple continents, showing how quickly viral pathogens can spread, especially through breeding colonies.

Because marine mammals often congregate in large numbers during breeding and molting, viral transmission can be rapid and devastating. In response to these losses, researchers have begun experimental vaccine trials in marine mammals. In late 2025, scientists administered an avian influenza vaccine to northern elephant seals, where vaccinated animals produced promising antibody responses without severe adverse effects. These trials represent one of the first proactive attempts to prevent disease, rather than respond to it, in wild marine mammal populations.

These efforts raise scientific and ethical questions. Researchers must determine which species would benefit most from vaccination, how long immunity lasts, and how to safely deploy vaccines in wild populations. Continued surveillance and research will remain essential, not only to respond to current outbreaks but also to anticipate future viral threats as climate change and other threats alter host–pathogen dynamics.

Why Microbes Matter For Marine Mammal Conservation

Microbes influence marine mammal health in ways that are often invisible but deeply consequential. Their impacts are closely tied to environmental conditions shaped by climate change, pollution, and habitat disruption. Because microbial communities respond quickly to these changes, they often reveal emerging risks before outbreaks and population decline are obvious.

The examples here represent only a small fraction of the ways microbes shape marine mammal health. From beneficial microbiomes to toxins, chronic disease, and emerging viral threats, these interactions prove the importance of exploring marine mammal microbiology deeper than surface level.

Incorporating microbiology into marine mammal conservation adds clarity to why animals become sick, stranded, or fail to reproduce, even when visible threats appear unchanged. Understanding these systems also strengthens conservation efforts by basing themin the biological systems that widely determine health and survival, more than previously thought.

Marine mammals have and will continue to draw our attention above the surface, but their futures are shaped by the microscopic world beneath it.

Image Credit

Thumbnail: Fur Seal in South Georgia, courtesy of Tiphanie May, @mayspeedwell